The Politics and History of Aerial Photos: Introducing Belle Park from the Air

My name is Francine Berish, and I work as a map and geospatial data librarian at Queen’s University. I'm also a proud collaborator on the Belle Park Project. I’m thrilled to introduce a short film, “Belle Park from the Air, 1924-2024,” a collective creation by Dorit Naaman, Laura Murray, and myself, with a captivating soundtrack by Matt Rogalsky. The soundtrack features underwater photosynthesis (!), nearby traffic, and plucked strings made from cattails.

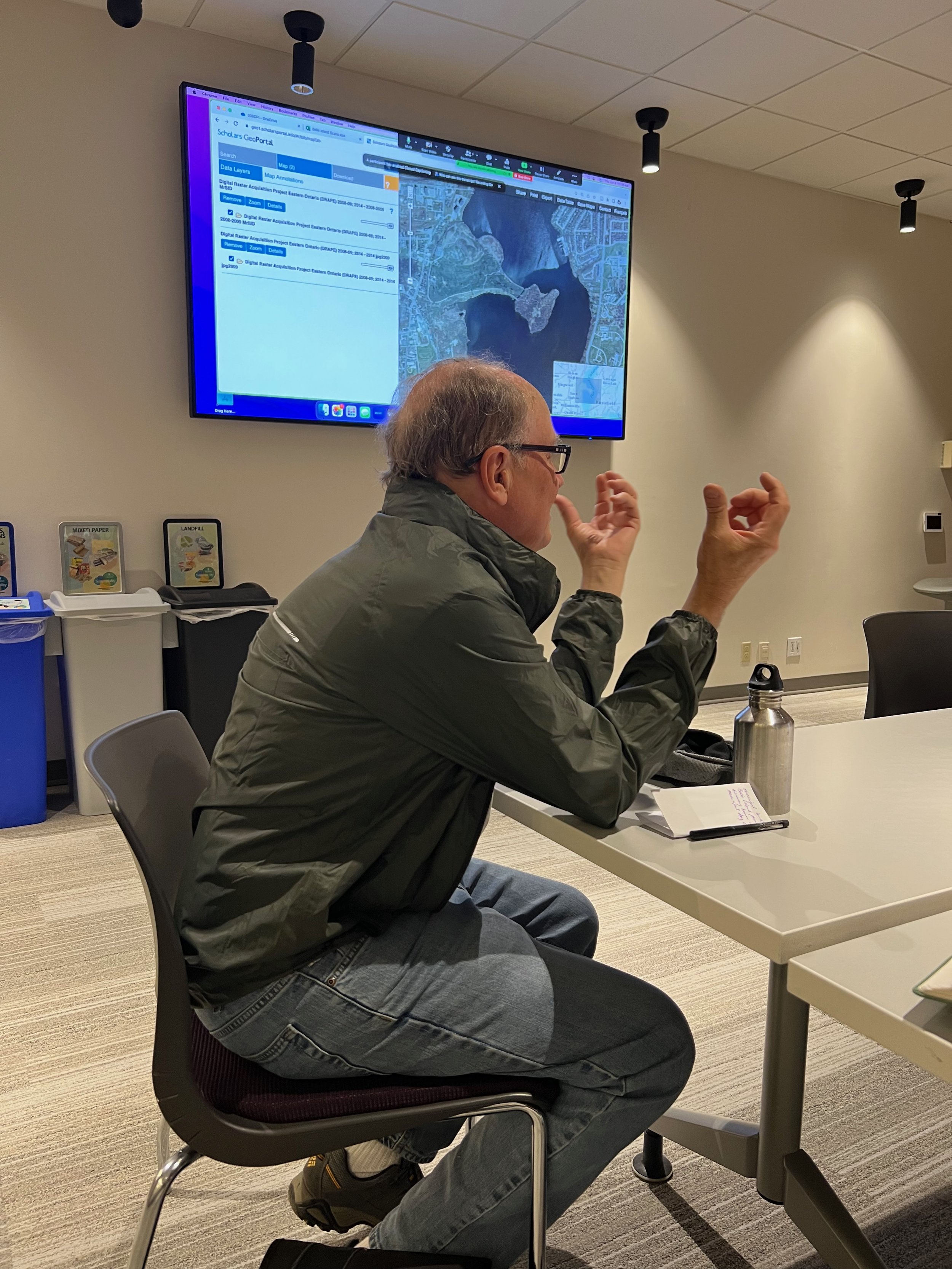

The initial goal of creating this resource was to help people imagine the changes to this place over the past century, by lining up or layering a series of aerial photographs. My role in the first instance was to gather the available resources from the Queen’s Library collection, but also to convene viewing sessions with the research team and community members to talk about what we saw, and what questions came up when looking at the photos. As we imagined how to present the material, Laura thought of it at first in the spirit of the “film strip” (an educational technology a few of you might remember if you went to school in the 1970s) or its equally retro living room analog the slide show (complete with slides you had to put in upside-down and backwards). But as you will see when you watch the final product, the series of photographs seemed to invite something of an artistic approach the more time we spent with them, and Dorit and Matt were really able to add that magic. We present the images in the end not only as information but as art, and we intend the video to encourage questions and critique, not just to convey facts.

One thing I enjoy about sharing aerial photographs with people is that it kind of blows their minds to see familiar places from above. After all, despite our familiarity nowadays with Google Maps, the view from above isn’t a “natural” way of seeing the land for humans, unless we are in an airplane or have a nearby mountain to climb. In fact, in the past and even today aerial photographs haven’t generally been created for the people who lived in the places they depict. In this blog post, I want to give a bit of background on the history, technology, and politics of aerial photographs, which we intend our film to push back against.

It was a balloonist and French photographer named Gasper Félix Tournachon (working under the pseudonym Nadar) who took the first known aerial photograph — over Paris in 1858 from a tethered balloon. As photographic technology advanced with the development of timing mechanisms, slow exposures, fuses, and emulsions, it became possible to fit cameras onto various flying objects like kites, pigeons (!), and, after their invention in 1903, airplanes.

During WWI, aerial photographs became a key tool in the production of maps and cartographic knowledge. When we think of World War I pilots we are likely to remember fighter pilots like Billy Bishop or the even-more-famous American ‘dogfighter,’ Snoopy. However, cartographer Gord Beck tells us that fighter aircraft were often only a means to clear the skies so that slower and less maneuverable reconnaissance planes could gather information to support on-the-ground strategies vital for winning the war. In war zones, aerial photographs replaced the work of the surveyor. By 1918, the British army had allocated almost 5000 troops to map production, and over 33 million maps had been printed (Beck 2014).

Unsurprisingly, as Collier points out, “After the war, new applications of aerial photography were quickly explored. Among the disciplines to benefit were archaeology, geology, physical geography, biology, and forestry” (2022). The Canadian government started systematically collecting aerial photographs in 1922. They became essential to the resource and industrial economy of Canada -- and, it should be said, essential to the colonization of Indigenous lands and water, because aerial photos and maps allowed the Canadian state and mining investors to see lands they had never been to, facilitating large-scale exploitation. Of course Indigenous people did and do have their own maps (see Indigenous Mapping resources below), but where in earlier eras would-be miners or loggers had to build relationships with Indigenous people in order to find resources and even to survive, aerial photographs allowed colonizers to ignore, bypass, or override Indigenous knowledge.

The oblique photograph with which we start our film was captured from the window of a plane in the Fall of 1924 by an unknown photographer from an altitude of 5000 feet (about 1.52 km). After 1924, most government-commissioned air photos were taken from a camera mounted to the bottom of the plane and show the park from an overhead angle. See here for a complete listing of sources for photos we have used. While these photos were taken as part of the system of economic development and state control I’ve described above, we use them to allow you to see the destruction of the wetland that is now Belle Park, and the persistence of Belle Island, a place of Indigenous habitation and use for centuries at least, and probably longer.

Today, governments and corporations alike commission air photos taken from aircraft, drones, and satellites. There is still great power in collecting and controlling the distribution of spatial information. Historically, governments or inter-governmental organizations have had data-sharing agreements at least with each other, but now industry and organizations like SpaceX and dozens of others with private interests have entered the arena. While their data could be free, it usually isn’t.

Making this film was a small attempt to subvert the military origins and capitalist functions of the aerial photograph. We aimed to mobilize this technology in caring and non-extractive ways, using it to learn or think about places and their complicated stories from literally a different perspective. Next time you visit the park you might be more aware of how it has been changed over time – both violently by the dumping of garbage on a wetland, and more organically by the abandonment of the golf course to the needs of plants and birds and unhoused people. You might also see how this place has resisted change. It still has the same shape, it still sometimes gets overtaken by water, it still has a lot more plants than people.

l like to believe that our use of the aerial photos in Belle Park from the Air hearkens back to the playful and artistic origins of aerial photography as practiced by Nadar, an artist, photographer, writer, and caricaturist. Other contexts might include historical and contemporary Indigenous mapping practices (see below). I have also been inspired by what Stephanie Springgay et al. (2020) call “anarchiving” — “an ethics based on response-ability, stewardship, care, and reciprocity that center relationships to land, territory, human, and more-than-human bodies.” This all might seem overly optimistic, in the wake of the recent Ontario Land Tribunal which threatens to “develop” part of the provincially significant wetland adjacent to the park. But I hope the film, with its meditative pace and sound, suggests that this place endures as itself, even when humans seek to capture, control, or destroy it.

Sources

Beck, Gord (2014). “Lens above Lens: The Development and Use of Aerial Photography in WWI.” Lecture. http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25366

Beck, Gord (2015). “Bleeding into the Margins: The Evolution of Cartography in WWI.” Lecture. http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25365

Collier, P. (2020). “Photogrammetry and Aerial Photography.” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition), pp. 91-98. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10583-9

Springgay, S., Truman, A., & MacLean, S. (2020). “Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation.” Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419884964

For a complete list of photographs used, see https://belleparkproject.com/projects/belle-park-from-the-air-19242024.

Some leads on Indigenous Mapping

Gaudry, Adam (2018). “Maps.” Foreword to the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, Canadian Geographic

G. Malcolm Lewis (1998). “Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans.” The History of Cartography, University of Chicago Press, Volume 2, Book 3.

Aboriginal Mapping Network — a project to put mapping in the hands of Indigenous communities