Belle Park Cattails 2: PSWs and Healing

I have been deeply grateful to a PSW these last several months. When I expressed this to a friend who knew that I’ve been healing from a messy break of my shoulder and hand, he assumed I meant my Personal Support Worker. Kristen was indeed a life saver but no, in that moment my thanks was directed to a ‘Provincially Significant Wetland’: the Greater Cataraqui Marsh PSW, whose southern edges are within walking distance of my home in Kingston. In Ontario, wetlands deemed “significant” are currently under extreme threat due to Doug Ford’s Bill 23 and the gutting of the evaluation system that has protected them from development. And the acronym slip/misunderstanding with my friend was hitting on a surprising reality: my PSW, that is, the Greater Cataraqui Marsh PSW, has in fact been playing the role of support worker in a personal healing process that of late has taken uncountable twists and turns.

Deep Hanging Out

If you read my earlier blog post, you will know about my affinity for cattails. Since the Belle Park Project began in 2020, I’ve been hanging out with cattails in the Greater Cataraqui Marsh, listening, sitting, wading, recording, in all seasons of the year. I’ve not been quite sure where I was going with all this, but I was inspired by Vinciane Despret’s notion of “visitation” as a field practice, and being open to any kind of connection or exchange. In this meditative space I was hoping for a form or feeling of reciprocity, a way I could give back to these remarkable beings who have been understood by Anishinaabekwe scholars as “land defenders” (Kaitlyn Patterson) that are “good for people” (Robin Wall Kimmerer) due to their sophisticated adaptations to marsh living. Not only do cattails protect shorelines from erosion, but their beings can transform into an astonishing array of “supermarket” provisions including shelter, food, clothing, lighting and medicine.

In the late summer of 2023, I caught the seed of an idea—or rather too many seeds for too many ideas. My sister, textile artist Heather Cameron of Gabriola Island BC, is part of the Fibreshed movement which seeks to redesign the global textile industry through place-based honouring of textile sovereignty, actively supporting local plants, people and practices. Inspired too by the outdoor artistry of Elaine Chan-Dow’s installation at No. 9 Gardens and Evalyn Parry’s “placefull” practice with life at Belle Park, I went to YouTube for training and soon found I had very basic skills to weave mats and to make cattail cordage – an ingenious Indigenous form of rope. The ‘plan’ kept elaborating but was initially about making a meaningful object from a cattail honourably harvested from each of three different locations in the PSW (Belle Park, Belle Island, and the Orchard Street Marsh in the former Tannery Lands). I went visiting with the cattails, made an offering, asked for their assistance, and, after further hanging-out, ended up bringing three of them home.

But what to make? And for whom? How did I want people touching them to feel? What is needed now? In the famous Fens of England where responses to climate change have led to new practices of wetland restoration and wet farming that are replacing centuries of wetland drainage, cattails have been identified as very good for certain entrepreneurial people: a new market and an “innovative new crop” for building materials, bioenergy and bioethanol. A profitable commodity wasn’t top of my to-do list, but I did consider what might be appropriate for here in some small way. A woven hat to shade a neighbour’s child from increasingly hot summers? A mat of cattail fluff ready to soak up oil spilled into Lake Ontario? A matching cattail apron and basket for a Belle Island Caretaker to use as he collects endless bits of styrofoam down-river from the Third Crossing? While these projects of my bleak imagination stalled with the start of a busy new semester, some sound experimentation with my partner Matt Rogalsky did demonstrate that finely twisted cattail cordage could be plucked, producing tones both guttural and velvety.

The Fall

But then came the 1st of October, when I fell from a height while pruning the maple tree. In my descent I broke bones with the fanciful names ‘humerus’ and ‘triquetrum.’ Sadly this strange new universe had little of delight to offer, even with the prescribed opioids. After a month the shoulder bone wasn’t mending on its own properly. It had to be rebroken and set with hardware that in x-ray resembled a medieval farm implement. Further setbacks early in 2024 involved continuing mind-body disconnections and unintended performance of slap-stick comedy: a parking lot control arm smashing me to the ground, and a spectacular tumble down my own staircase.

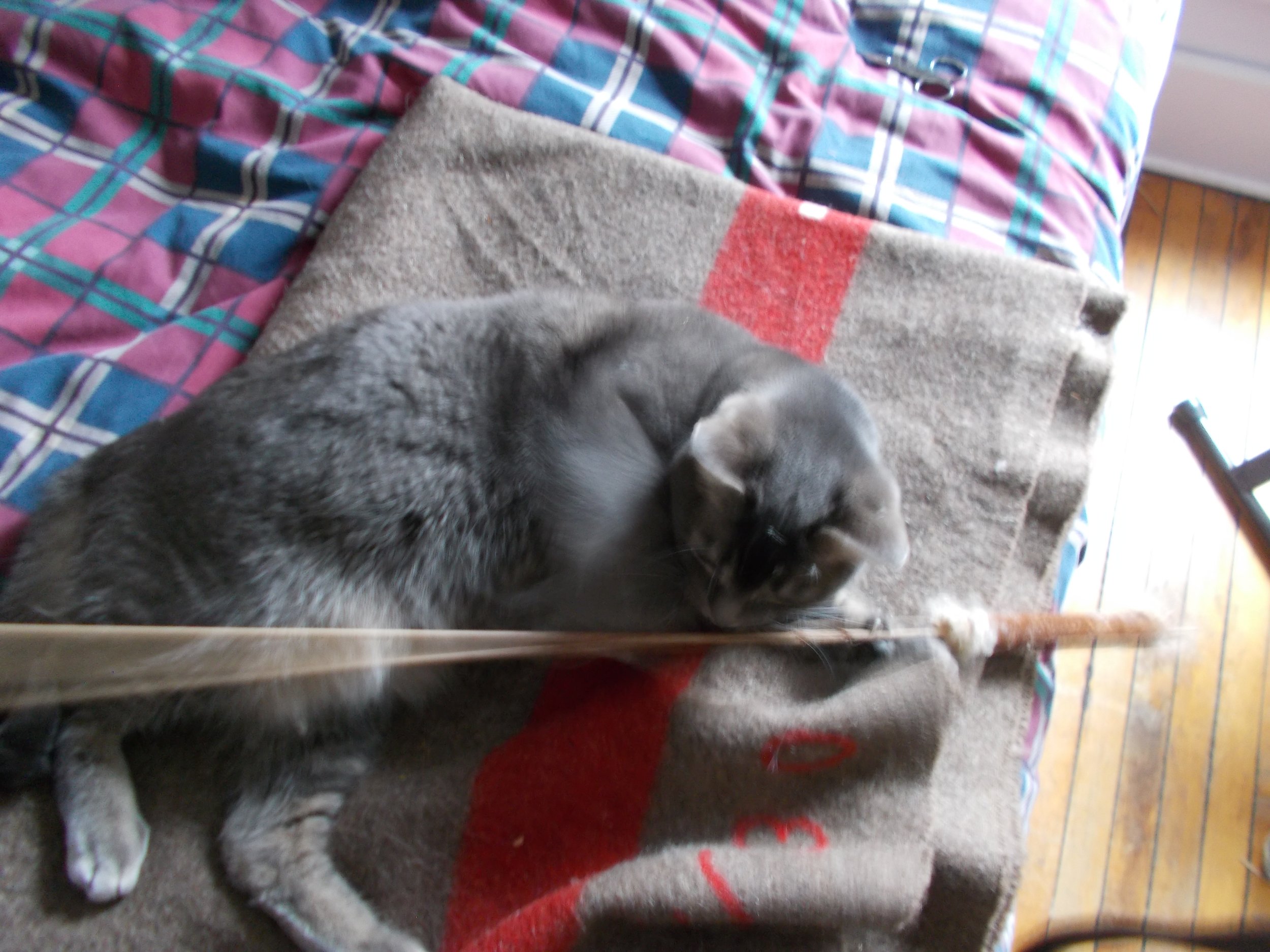

My left arm and hand became useless to me for the most mundane tasks, let alone a crafting project, and I might have forgotten about the cattails altogether, but our cat Robin did not forget about them. Cattails were her favourite plaything and became her frenemies to wrestle with or an imaginary kitten to carry about the house. I had been a bit anxious about her contact with the cattail from the Orchard Street Marsh because of the marsh’s history as an outlet for the toxic wastes including heavy metals like chromium and lead, but Robin was clever and relentless and, in her play, kept slipping past apparently closed doors. Finally, I securely locked everything away, but my piles were no longer tidy and the idea for three distinct ‘art objects’ associated with three different cattails from three different places was now one jumble in a mind that was not dealing so well with some of the worst pain of my life.

Changeroom

It was in this dark time that I encountered Carleigh Milburn, an Indigenous artist and scholar. She had assisted the Belle Park project with research in the midst of the pandemic when we were all meeting on Zoom, but at this time I ran into her in a non-virtual gym where I flailed with my physiotherapy exercises. When I mentioned in passing that I was stuck with my cattail project as well as with the frozen shoulder, Carleigh started talking about her approach to art and relationships with land and water, how it’s all about healing and gratitude. Her changeroom words sunk into the mucky heart of what I wanted to do and when I went home, I started talking with the cattails again.

Yes, the piles were messed up, but what did my original categories matter anyway? These wetland places were all part of the Greater Cataraqui Marsh, and in fact, cutting up the marsh into parcels with property boundaries had been the opposite of what made for flourishing. I wanted to honour the life interweaving these places, not separating them. And instead of pulling out the best parts for cordage, I now felt gripped by an imperative to connect with as much of the cattail as possible, not divide parts into ‘useful’ and ‘useless.’ The PSW was making a home visit with these cattails: I was lucky these beings were here at all, and I only had just started to get to know them. With my hand still clumsy and only starting to ‘wake up,’ my cordage, requiring two hands to make the twists, was never going to be fine and regular. This would be a process that might weeks or months. But every day, as my hands made the twists and turns for a little bit longer and with a little less pain, the cattails began steadily, patiently, healing me.

As we created together, the cattails became teachers, a cattail profession that Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about. I learned that in soaking the dry cattail leaves to make them pliable, the antimicrobial substance that keeps the cattail wet when water levels fluctuate in the marsh returns to its original jelly form. Although it was surprisingly slimy at first, working with this stuff that Kimmerer calls “the swamp’s answer to aloe vera gel” left my hands feeling really good: “the same properties that protect the plant protect us too.” At the same time, I was still uncertain about potential poisons in the cattail leaf blades that came from the former Davis Tannery lands. Cattails are employed worldwide in phytoremediation strategies due to their ability to grow in heavy-metal polluted environments: the secret of their astonishing ability to remove metallic ions has to do with all the airy spaces within their structure. So, maybe I had good reason to worry.

But Carleigh’s response was that her art practice engaging with museum objects had taught her that objects will tell you if they are ready to be worked with: they will respond to your questions and they can say ‘no.’ And perhaps I had my answer already: I wasn’t getting a rash, Robin the cat remained obsessed with the cattails, and my hands felt better every day. Still, because I knew Graham Cairns, the affable Director of the Queen’s Analytical Services Unit, I asked him to run some laboratory tests on part of a cattail that still held a label identifying it as being from the Orchard Street Marsh. The result: “Nothing in the mercury report and nothing of note for the ICPMS (27 element) report.” Neglible for heavy metals. Robin and I could probably eat these cattail leaves and be okay. But why was this? Maybe the marsh wasn’t contaminated where this cattail was living. Or maybe Robin and I had been benefitting from the marvelous fact that while cattails are highly efficient at accumulating heavy metals in their roots, they have the ability to not translocate heavy metals beyond their roots, leaving their leaves and flowers free of toxins.

The Tribunal

Over the past three weeks I twisted and turned cattails as I watched the Ontario Land Tribunal bring out witnesses for cross-examination. I felt a bit like Madame Defarge with her knitting though it was not me seeking to condemn fellow beings to a deadly fate. Many witnesses affirmed the significance of the Orchard Street Marsh, one ecologist calling it “a high value, high functioning PSW. A little gem within the city, that is used as a residence by many wildlife species.” Another singled out the cattails for special praise: they are growing really well and have a “stabilizing effect” on the site. She related too that muskrats eating the cattail roots are unaffected by chromium because the cattail roots keep it immobile and in a form that won’t do the muskrat any harm. So much internal magic.

If parts of the wetland are contaminated, can they be restored after remediation? Yes, is the answer. And yes, I shout into the air, after all the extractions, destructions and pollutions of wetlands here and everywhere, and with all they do for the creation, maintaining and healing of life on wet planet Earth. Yes, absolutely, they should be. My role? I’m not 100% sure but as the PSW helps restore me to health, it is much harder to just turn away. In creating and healing together, the cattails ask something of me too. How will I draw on my own internal powers to help support life?

Final installment coming soon: “The Dragon Rises”

Notes and Resources

Haraway, Donna, A Curious Practice, Chapter 7 in Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Kimmerer, Robin W. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Martinez-Martinez, Joana Guadalupe et al, “Bacterial Communities Associated with the Roots of Typha spp. and Its Relationship in Phytoremediation Processes,” Microorganisms 2023, 11(6), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11061587.

March 8th was the final day of the Ontario Land Tribunal hearing. We await the decision.

You can read Vicki Schmolka’s excellent daily summaries at

https://vickischmolka.substack.com/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email