Belle Park Cattails 1: A Cluster of Cat-tales

For as long as I’ve loved wetlands, I’ve had a thing for cattails. Whenever I encounter them up close, usually in my rubber boots or hip waders, I’m struck by their beauty and tenacity. But as a historical geographer, I’m aware of their historically marginalized status – a status that tends to stick. That is to say, like the wetlands they inhabit, cattails have not been considered useful or “productive” in the colonial quest for property and farmland. The homes of cattails have been derided, drained, destroyed and forgotten. 70% of Ontario wetlands are already gone. But the more one learns of the endlessly giving natures of cattails, the more one yearns to be in their company. Like all beings under the sun, they have stories that change with place and with period — beyond-human stories that urgently deserve wider attention.

In fairy tales, the number three figures prominently: three siblings, three tasks, three magical gifts. The same is true with cat-tales, it seems. To launch my three part series on the Belle Park cattails here in Kingston, I offer three small stories connecting three contiguous places: (1) Belle Park, (2) Belle Island to the east, and (3) the former Tannery Lands to the south (including the Orchard Street Marsh).

Ontario GeoHub, 2 Feb 2024. Red indicates an area of provincially significant wetland, the Greater Cataraqui Marsh. Note that this map reflects changes made to the PSW boundaries in the Tannery Land property by an OWES evaluation submitted in November 2023.

Cattails are “obligate” plants which means that they are always found near water. Known as “cumbungi” in Australia and “soli soli” in the Phillipines, they live in wetlands all over the world. They belong to the genus Typha, a Greek word first used in print to refer to cattails by Theophrastus (372- 287 BCE). Scientists have differentiated about 30 species of Typha worldwide. Three commonly living in the wetlands of Southern Ontario are the broadleafed Typha latifolia, the narrowleafed Typha angustifolia, and Typha x glauca, a hybrid of the two. But perhaps more significant than the distinctions are the ways that all cattails offer a similar range of gifts. The Anishinaabemowin name addressing cattail kin, “Apakweyashk”, and their Kanyen’ke:ha name “Aotáhsa,” both recognize beings, not species or types. Mandy Wilson of the Kingston Native Centre and Language Nest regularly teaches about this amazingly versatile being as a source of medicine and food that can also be used in making furniture, baskets, insulation, cordage (rope), and clothing. Cattails are also champion cleaners and remove polluting materials from their environments. So it turns out that not only are these “obligate” plants dependent on water, but water is “obligated” to them as well.

As a former professional cleaner myself, it is cattails’ work as “cleaners” that really raised my protective passions. They do the feminized work of maintenance that is classically devalued and poorly rewarded. When I joined the Belle Park Project, I promised myself hand on my union-maid heart that I would do something with cattails.

So, to begin this honouring, once upon a time….

(1) Cattails to the rescue at Belle Park

The 44 hectare city-owned Belle Park was wetland before it became the city dump in the 1950s. The refuse and fill raised the height of land near the shore, and, as you can imagine, this was not so great for shallow-water loving plants like cattails. The garbage also was not good for the health of the Cataraqui River, and in 1997 Kingston citizen Janet Fletcher raised the alarm on behalf of the river. Jump ahead to 2003, when the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld a number of convictions against the City of Kingston under the federal Fisheries Act, and a company had been contracted to explore ways to reduce the contaminants leaking into the river. Suddenly cattails were seen as rescuers, and summoned en masse to assist with phytoremediation. According to the engineer’s report, a substrate mattress was constructed to “serve as a platform for native wetland species, such as cattails, to grow and to establish a wetland buffer zone adjacent to the landfill site. The wetland buffer zone would then act to reduce/attenuate contaminants from diffuse landfill seepage into the Cataraqui River” (1-2). The cattail mattress sank during the Spring flooding of 2005, but there are other areas in Belle Park, such as within the bermed area constructed for dredged contaminated silt on the north shore, where cattails currently thrive along with what biologists call an astonishing variety of other forms of life.

(2) Cattails and Miss E.E. O’Gorman at Belle Island

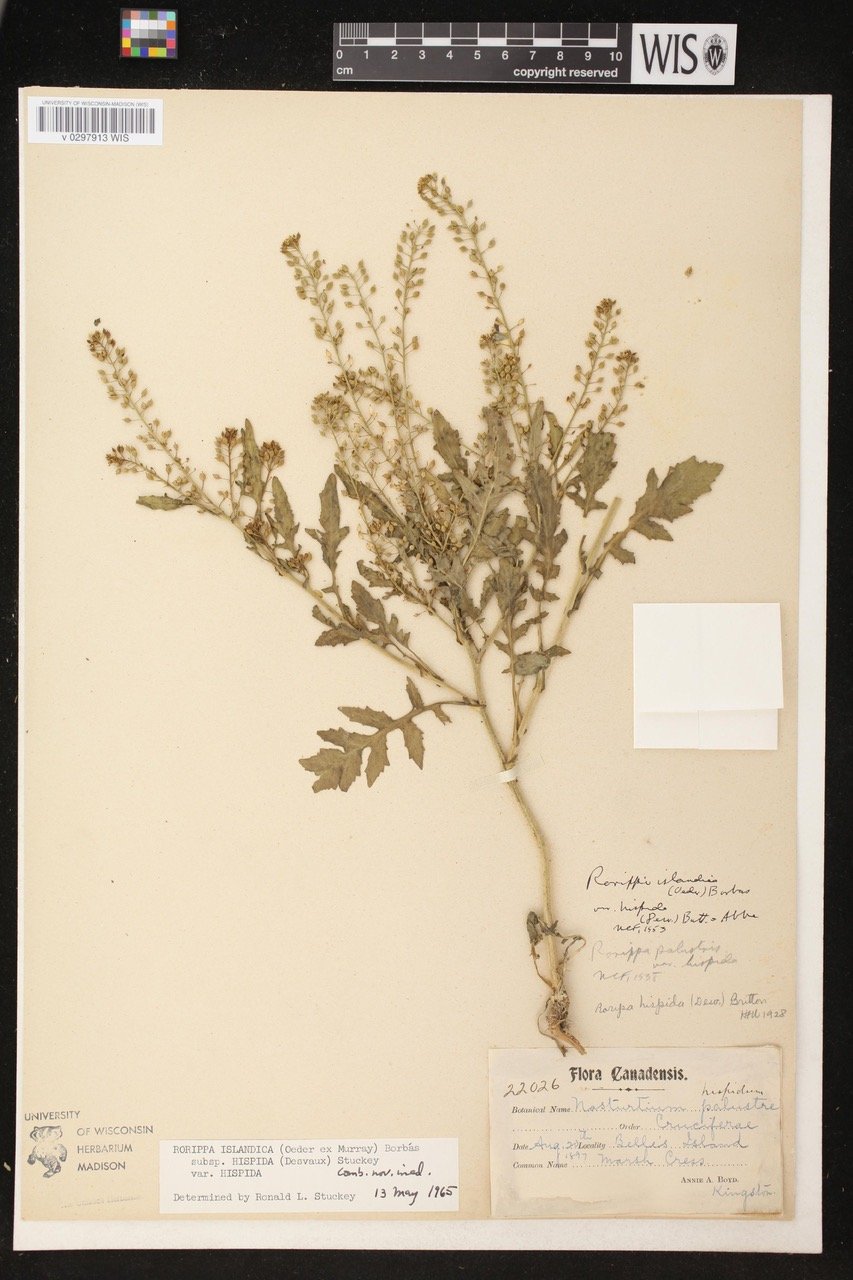

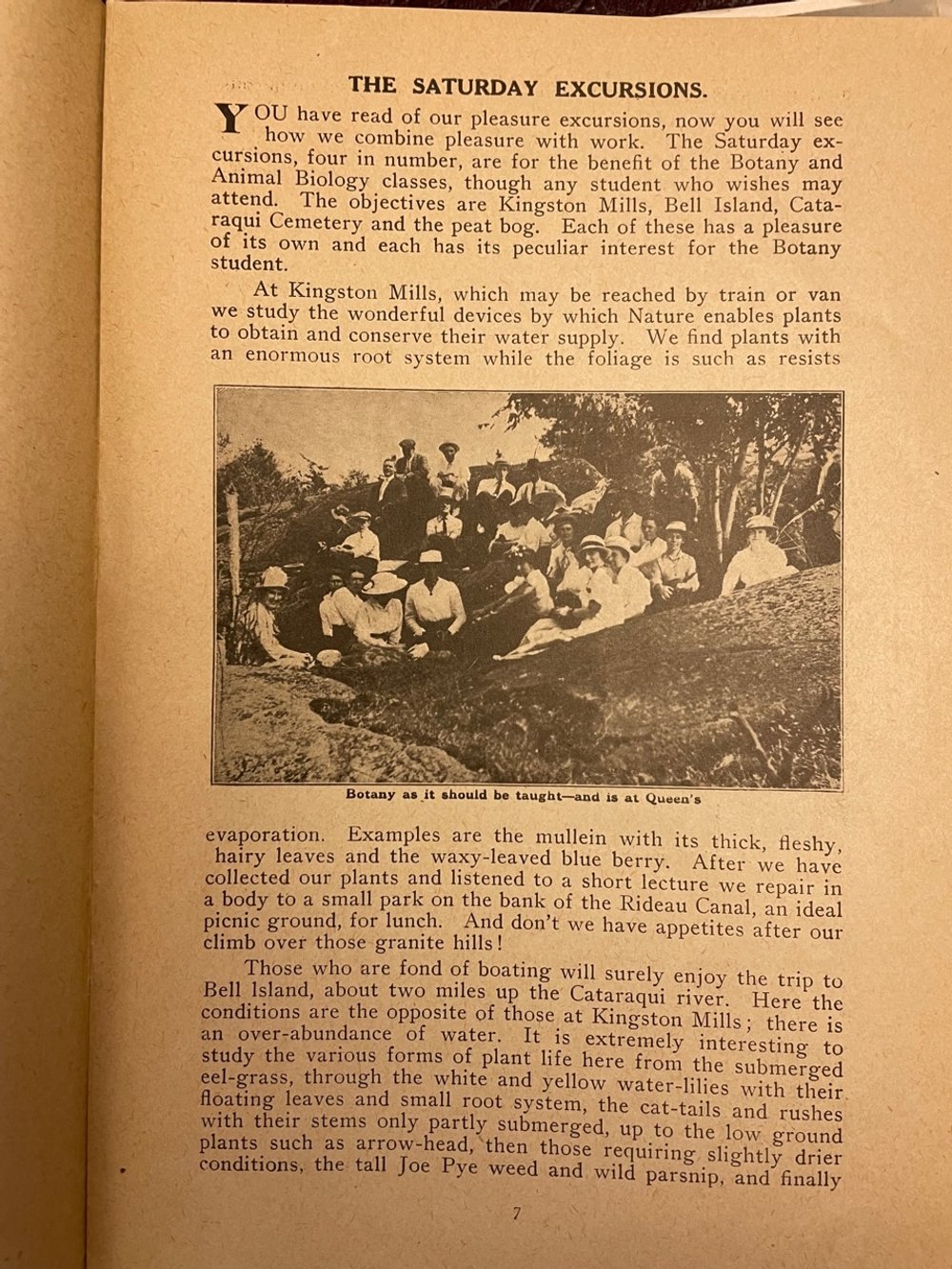

Belle Island (12.4 hectares) is a sacred place co-owned and co-managed by the city and the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs. It used to be connected to the riverbank by a wetland, and now it is connected by Belle Park, the former landfill. It has a very long history of Indigenous human presence and thus a very long history of stories and storytelling. Much more recently, Belle Island has also been visited by white settlers (of which I am one), including naturalists keen to study wetland vegetation. In 1897, the botanist Annie A. Boyd collected from the island a specimen of Rorippa palustris (the latter term meaning ‘of the marsh’), otherwise known as marsh yellow-cress (see image). Around 1915, the Queen’s Biology Department began bringing students to Belle Island as part of a Summer School program led by Professors William MacClement and Rollo Earl. They came by rowboat, as future Belle Park was still fully wetland and inaccessible by foot. In an account written by a participant, Miss E. E. O’Gorman of the “Seed Branch” of the federal Department of Agriculture, cattails are explicitly mentioned (see image) amongst an abundance of life forms: “it is extremely interesting to study the various forms of plant life here from the submerged eel-grass, through the white and yellow water-lilies with their floating leaves and small root system, the cat-tails and rushes with their stems only partly submerged, up to the low ground plants such as arrow-head, then those requiring slightly drier conditions: the tall Joe Pye weed and wild parsnip, and finally high ground plants, fleabane, May apple and others too numerous to mention.”

(3) Cattails in a Provincially Significant Wetland, the former Tannery Lands

One may still visit with Belle Island cattails, and, as I mentioned in the first story, cattails thrive in the contaminated silt within the berm of Belle Park. Their wetland homes are part of what has been designated by the Province of Ontario as the Greater Cataraqui Marsh Provincially Significant Wetland (PSW) and they are themselves significant members of this marsh ecosystem, which extends from the upper end of the Inner Harbour (roughly across from the Woolen Mill) northwards up the Cataraqui river to the 401. A PSW is a wetland that the province considers most valuable using a science-based ranking system called the Ontario Wetland Evaluation System (OWES). A PSW — and the cattails within — are protected from development. This is particularly important for my last story about the cattails living south of Belle Park in the 14 hectare developer-owned area known by its previous industrial use as the “Tannery Lands”. These cattails occupy the Orchard Street Marsh which is also part of the Greater Cataraqui Marsh PSW. Here in the Tannery Lands, they are vital members of a plant community that includes a forest of more than 1800 mature trees graced by a healthy grand oak over 200 years old. Its roots, as the late Laurel Claus-Johnson reminded us, extend into the shoreline’s “ribbon of life.”

Globally, wetlands are seen as hugely important for carbon capture to mitigate climate change — even more important than forests. Also globally, tanneries are extremely polluting with their use of heavy metals and other dangerous toxins, and their treatment of waterways as sewers. Locally, we see an example of the wetland fighting back — as wetlands do. Lo and behold, the cattail clean-up crew arrived on their own without special summoning, and have long been applying their healing wisdoms that include the phytoremediation of land and river contaminants.

The developer has shown little interest in the value of cattails and, rather, has sought to remove wetlands within the property from protected designation. Last year, the City of Kingston voted to reject the request for zoning change and the development plan which would destroy the biodiversity here. The developer appealed and on Monday, 5th February this year the Ontario Land Tribunal began meeting to consider the case. A Land and Water Tribunal would have made more sense, but illogical colonial terms prevail, in which land can be “reclaimed” (not, more accurately, “claimed”) from wetlands for the making of property. And since the passing of Bill 23 and the vast overhaul of the OWES which came into effect in January 2023, it is increasingly difficult to protect any wetlands in Ontario as significant. This stand of cattails, arguably doing some of Kingston’s most vital work, joins the ranks of the highly endangered.

But for now, I choose to end this third story, like the others, in an astonishment of interconnected life. Listen for yourself to beings “too numerous to mention.” This is spring with the cattails, in the Orchard Street Marsh:

Notes and Resources

Even if you are not a registered Participant at the Ontario Land Tribunal, you can still watch the proceedings on YouTube here. They are likely to continue every day until the end of February 2024 at least.

Ontario GeoHub for Wetland Significance (sign-in required)

Belle Park Landfill, Assessment of Long-term Management Alternatives, 2006

Patterson, Kaitlyn, “Who are the Cattails? Stories of Algonquin Anishinaabe Food Systems,” Canadian Food Studies, 8:1 (2021) 22-28.

See Helen Humphreys, Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium (ECW 2021) for a portrait of Annie Boyd and other plants she collected. According to Anna Soper, the specimen sheet currently held at the University of Wisconsin appears to contain a packet of seeds.

The Summer School Bulletin is held by Queen’s University Archives; thanks to Heather Home and Deirdre Bryden.