Totem Pole

At the entrance to Belle Park, just off Montreal Street in Kingston, Ontario, there stands a peculiar sight for eastern Canada: a totem pole. Made from a cedar log gifted by the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, the pole was carved by members of the Native Brotherhood at Joyceville Correctional Institution in 1973. Presented to the City of Kingston by the carvers to commemorate the 300th anniversary of colonial presence in the area, the pole clearly meant something else to the carvers. As spokesman Charlie Hill said, “We do not celebrate 300 years — that is yours.” For Hill, the pole represented a demand that “the people of this area give respect to our people.” Details of the pole and statements from other carvers indicate that it holds stories, histories and contemporary realities of those who carved the pole. But totem poles are rooted in Northwest Coast cultures and associated with political and cultural practices and traditions that the carvers of this pole probably knew little about. What are the most appropriate and productive ways to think about and engage with this pole today? How might it present an invitation to grapple with histories and futures of this city in which it stands as the only public monument to Indigeneity? What are the challenges it poses? What are the relationships it may represent or enable? What would it mean to care for the pole? It is not for the Belle Park Project to answer these questions — and there are many more of them no doubt — but we seek to facilitate discussion and engagement, bringing together local Indigenous perspectives, archival and historical sources, Northwest Coast cultural knowledge, artistic practice, and more. For some of our initial questions and thoughts in May 2021, see this video.

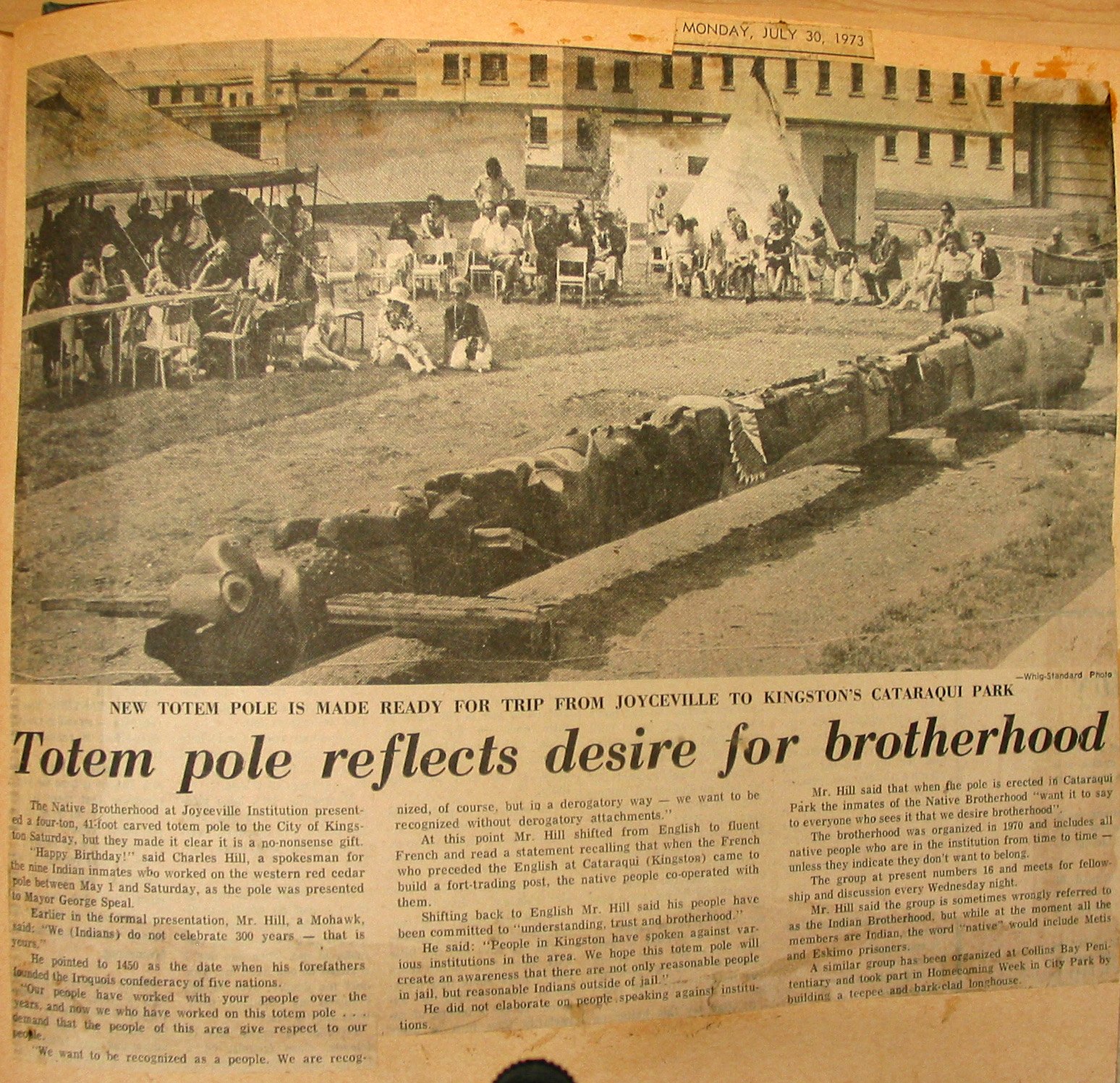

Whig Standard 30 July 1973, courtesy Queen’s University Archives

Photo taken at Joyceville Institution. Note tipi and canoe as well as the pole with wings on top figure (now missing).

“We do not celebrate 300 years — that is yours... Our people have worked with your people over the years, and now we who have worked on this totem pole... demand that the people of this area give respect to our people.”

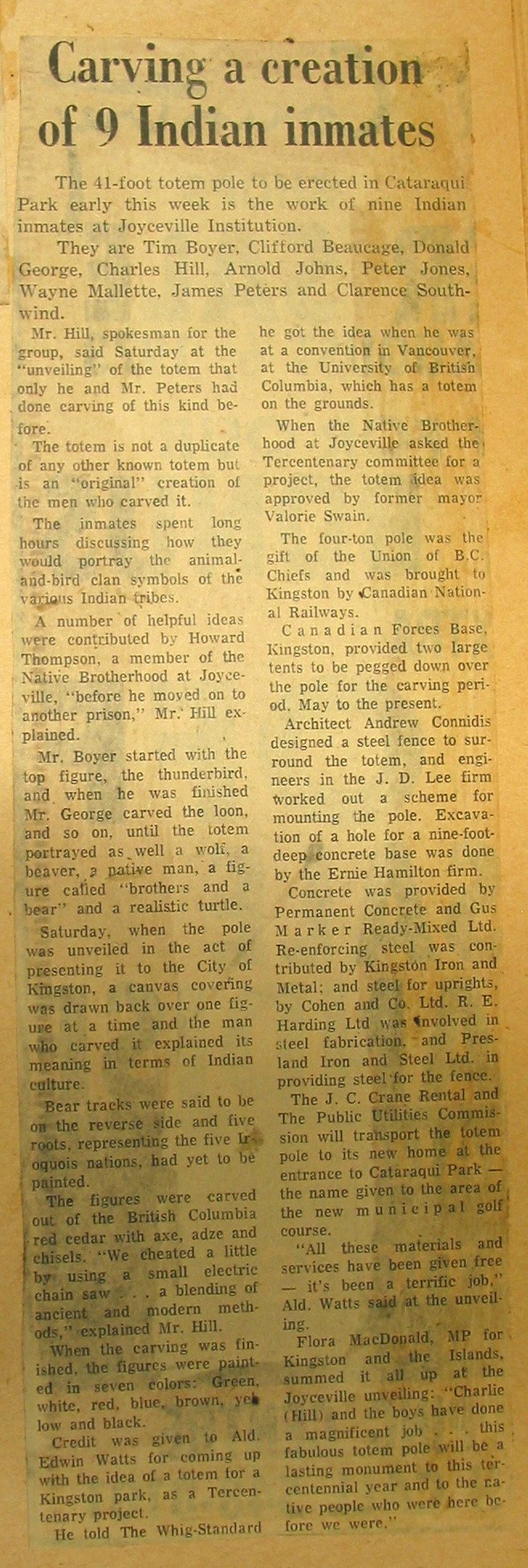

Whig Standard 2 August (?) 1973, courtesy Queen’s University Archives

“Figure No. 5 — called a NATIVE MAN. Peter Jones, the craftsman, explained that the war bonnet represented in the figure differs from tribe to tribe. The figure holds two poles in his hands — part of the pole itself, carved so as to appear free-standing. The ‘cappings’ on these poles, looking like crowns on two staffs represent to Mr. Jones the monarchy in past years and the present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. Around the feet of this figure are smaller symbols — bear, buffalo, snake, deer and wolf — all with clan meanings.”

Whig Standard 2 August (?) 1973, courtesy Queen’s University Archives

“Sonny Garrow explained that the symbols of bear tracks, gouged and painted on the back of the totem pole, represent the ‘spiritual force of Algonquin people, all across North America.’ This symbol was incorporated in the totem to represent a binding together of all the symbols on the face of the totem. Five roots... at the base of the totem, represent the Five Nations in the Iroquois Confederacy. The roots represent also the tree of peace, said James Martin.”

Whig Standard, 30 July 1973

“The totem is not a duplicate of any other known totem but is an ‘original’ creation of the men who carved it. The inmates spent long hours discussing how they would portray the animal-and-bird clan symbols of the various Indian tribes... the figures were carved out of the British Columbia red cedar with axes, adze and chisels. ‘We cheated a little by using a small electric chain saw... a blending of ancient and modern methods,’ explained Mr. Hill.”