Where Does Kingston’s Garbage Go? Part One

August 18, 7:30 a.m. Steel-toed boots and snacks at the ready, Matt, Laura M and I pile into Mary Louise’s car on our way to find out where Kingston’s garbage goes. That means my personal garbage too, it should be noted: the odorous mélange of irredeemable and unspeakable things, mostly unrecyclable packaging debris, that went out to the curb last week in my ‘GoodSense’-branded trash bag. Where does it end up? We want to know. Sixty years ago, the solid waste of Kingston’s citizens, institutions and businesses would have been dumped into the wetland between the riverbank and Belle Island. As we learn more about the landfilled marsh, now Belle Park, we’ve had a growing sense we should know if our garbage nowadays is treated any more responsibly.

But the forever resting place of our Kingston collective crap has remained mysterious. Off and on, we’ve been asking around for some time now. On the one hand, it seems to us disturbing and almost suspicious that this information isn’t an easy web search away, but we’ve also taken it on in the spirit of a treasure hunt – a quest. Recently, a helpful City employee came up with the name of a location: Moose Creek. And the landfill folks agreed to give us a tour. So we’re on the road. Passing through green fields, brown fields, past Gravel Road, Sand Road, somewhere north of Cornwall and Akwesasne, we arrive at GFL Moose Creek, our little car entering the landfill site along with a continuous stream of enormous but otherwise unremarkable and unlabelled trucks containing who-knows-what.

Our guides, Greg and Prashant, are waiting for us and very eager to explain how the landfill works. GFL, we learn in the course of a Powerpoint presentation, stands for “Green For Life Environmental Inc.” It’s the fourth biggest waste management company in North America. The branding on signs, business cards, trucks, shirts, is delicate light green – the colour of fresh unhusked corn. The smell in the air suggests, but only suggests, something else: the something else we're looking for.

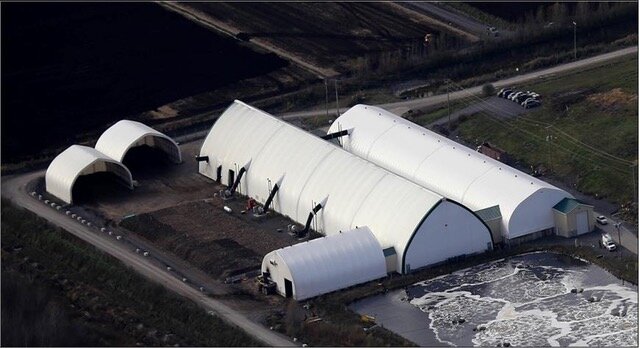

We try to absorb the numbers. This solid non-hazardous waste landfill, which sits on and near the Moose Creek Bog, serves 500 municipalities and is nearly full. Of the property’s 953 hectares, only 189 hectares are currently approved for active landfill. Opened in 1999, that portion of the site currently has four or five more years of “life.”

Every day, 2.5 million kilograms of garbage is squeezed out of the back of trucks at this site, and every night it is covered over by a fresh blanket of contaminated soil (a bountiful resource of our region). The landfill rests on a natural clay bed. When a section is 16 metres high, it is sealed with a plastic liner. A layer of sand followed by twelve inches of uncontaminated soil completes the cover, and an emerald-green dusting of coated grass seed makes the mounds verdant before the grass even sprouts.

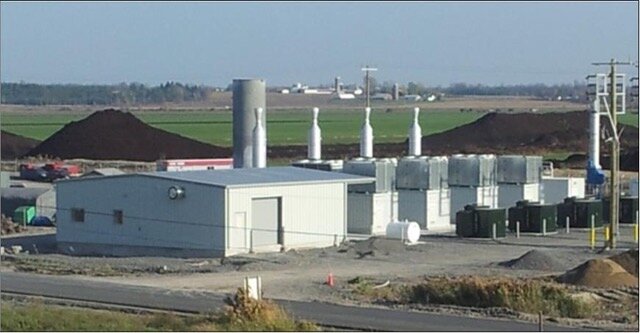

The potion of methane and CO2 brewed in this anaerobic pressure cooker is collected by dozens of gas wells and piped to power generators that create electricity. If expansion is approved, GFL hopes to be able to heat 20,000 homes for 5 years from this landfill at peak methane production around 2027-28. Leachate is collected and treated onsite before being released into Moose Creek. GFL also makes compost here that is sold at garden centres under the “Scott’s” brand. The compost building is the part of the landfill that really stinks (rather like toxic olives) – and while it is shocking the large amount of plastic packaging we can see in the raw food waste, the finished product is warm, smooth, and crumbly.

As Prashant drives us in a bus around the site, we watch – and hear – the compactors, loaders, dozers, and rock trucks, grunting and roaring like mythical creatures smelting and guarding their treasure. We have no difficulty believing that this landfill is state-of-the-art. But our thoughts go to flesh-and-blood creatures, the gulls mobbing the dozers, the groundhogs and worms that must be challenged by the plastic layer beneath us. They are outsiders here. From the landfill’s standpoint, gulls are pests, corrosive to an image of being sanitary. Greg tells us about the Harris’s Hawks, Mrs. Doubtfire and Gwyneth, brought by falconers to the landfill to frighten the gulls away.

We wonder too about the mostly drained bog and its peat and topsoil that continue to be extracted nearby and sold. Moose Creek Bog stories are hard to find. A 2018 environmental assessment report refers to the bog as “peat and muck.” Was Belle Park marsh once called “muck”? All over the planet, despite their own magical powers related to biodiversity, healing and carbon storage (peatlands in Ontario alone store about 28.2 gigatonnes of carbon), wetlands have been devalued, drained, mined and filled in.

We are uneasy about the whole experience. Yet without a doubt, as Greg says, “we at GFL don’t make the garbage.” The landfill, we are told, contributes to the circular green economy — which, in order to keep going, must keep growing. Thus, the circle would be better described as an ever-widening and ever-deepening spiral. “The ceremony of innocence is drowned,” and we are all in the thick of it in everyday actions of disposal. Other lines in Yeats’s poem hum in my head: “Turning and turning in the widening gyre/ The falcon cannot hear the falconer.”

Well, at least we know where our garbage goes.

Or do we?

Upon our return, our contact at the City apologizes and provides new information. While it has gone to Moose Creek at some point in the recent past, our garbage currently goes somewhere else.

What?!?!

Stay tuned for the next installment when we go in search of another landfill, by another creek, far far away from Kingston.

—with thanks to Greg van Loenen and Prashant Vats at GFL Moose Creek, Adam Mueller at the City of Kingston, and Elizabeth Nelson for research assistance. Gratitude as well for the input of editor Laura Murray, fellow travellers Mary Louise Adams and Matt Rogalsky, and Dorit Namaan, who missed this adventure but will join us on the next one.

Images:

1. Aerial view of the facility and surrounding property. Credit: GFL

2. Onsite energy facility that uses the landfill gas to power generators creating 4.2 MW of electricity. Credit: GFL

3. Onsite composter that processes over 100,000 metric tonnes of organic waste per year. Credit: GFL

4. Atop the landfill. From L to R: Matt Rogalsky, Mary Louise Adams, Laura Murray and Laura Jean Cameron.

Resources:

Myra Hird, Canada’s Waste Flows (2021)

Robin Kimmerer, “The Red Sneaker,” in Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (2003), pp. 111-120.

W.B. Yeats, “The Second Coming” (1919)

OWMA, State of Waste in Ontario: Landfill Report, January 2021