LAWNCARE: Notes on Art and the Politics of Maintenance

From Hazard to Feature

Tape measure, flagging tape, water.

Lawnmower, brush cutter, ear protection.

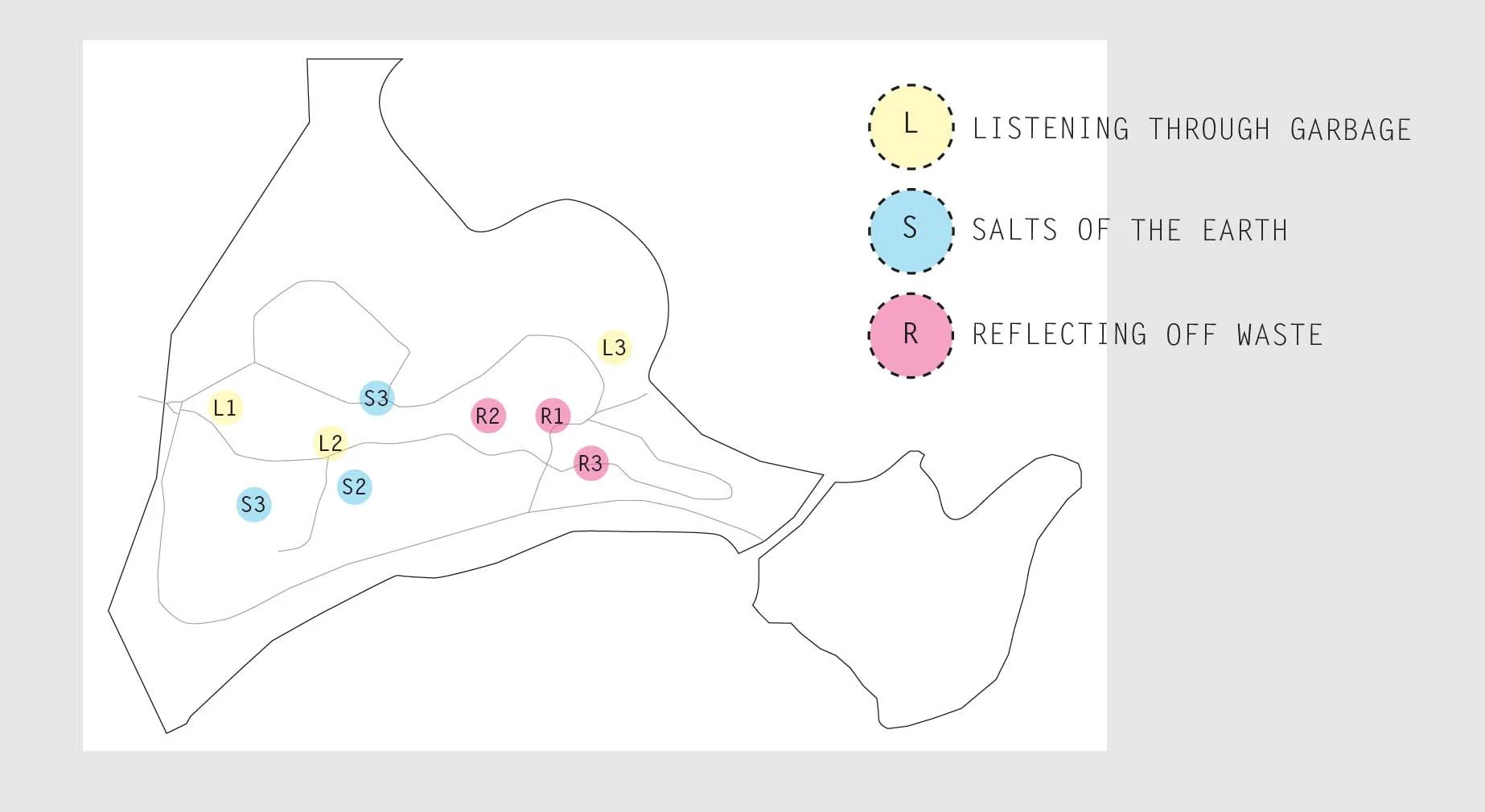

It’s morning, earlyish, and I arrive with the tools, the plan, and a head full of anxiety. Is this actually going to happen? It’s a question I have been engaged with, perhaps even struggling with, throughout the preceding weeks, as logistical complexities and bureaucratic challenges have filled the space where pure creative joy and artistic fulfillment might otherwise prevail. The concept for the artwork is simple if labor-intensive: nine sculptural flags installed across a large municipal park that had once been a golf course, now overgrown with tall grasses and burdocks, and home to coyotes and unhoused humans alike. My idea was to evoke the park’s golfing history and prior use as a landfill through a custom network of clearings and paths — an alternative choreography of the site, drawing attention to its entangled and overlooked pasts. Okay, maybe not simple, but possible… right?

Luckily, I have a crack squad of volunteer landscapers (shoutout to Jack Fitzgerald, Matthew McCarthy, and Benjamin Hackett), a small crew of devoted helpers experienced in the dark green arts of large-scale gardening, and open to a project with a twist. I am deeply appreciative of their generosity (they were compensated only in pizza), and grateful for the paucity of other summer jobs available to late high-schoolers and early undergraduates in need of beer money —and rent — which prepared them well for such endeavours. Now these skilled landscape artisans are my collaborators, and we set out into the Park motivated by something greater than hourly wages. Together, we create the artwork over two long days: mowing, trimming, and sweating in the late summer heat. Partway through the install I realize just how integral this group undertaking is to the overall meaning and substance of the project — a kind of artistic performance in its own right, full of gestures, shouts, and humour.

Care as a Form of Harm

The artwork is a temporary public installation called LAWNCARE. It’s a multimedia project I described at the time of proposal as “a series of site-specific interventions that takes as its starting point the forms of attention that shape landscapes according to specific personal, collective, and institutional desires and protocols.” Within this conceptual framework, attention is linked to the notion and practice of care. But care in the context of landscape transformation can be as full of violence as it is of love, and historical transformations at Belle Park include successive regimes of landfilling, golfing, and now remediation. Responding to the specific conditions of the site, but also to broader questions about how artificial ground is made (see Edgeworth 2014), Lawncare engages “the lawn” as a phenomenon not found in nature, but actively produced through the complex interplay of culture, ecology, and politics, and the project set out to consider how the care it receives reflects the societal values of a given time and place.

As a former architect who once spent a year designing a long-distance hiking trail connecting Algonquin Provincial Park to the Adirondacks in upstate New York, I come to working at the scale of landscape with an ongoing interest in the horizon, its image, and the various pathways one might take to get there. However, as my interest in landscape — both as concept and as place — has deepened, I have found myself increasingly drawn not to the horizontal surfaces and views typical of painting, photography, or cartography, but toward the vertical: the z-axis of three-dimensional space. This orientation challenges conventional forms of representation and exceeds the limits of human vision, extending into realms where so much remains unseen. The ground itself is thick; it is often below the surface where matters of politics, ecology, and time converge and intermix. This is especially true at Belle Park, a site that was once a wetland before being converted into a landfill in the 1940s and later, in the 1970s, transformed again into a golf course. Belle Park stands as a potent symbol of the layered and recursive processes that drive environmental change — processes that are spatial as much as they are historical and ideological.

Unearthing Narratives

Above ground, the poplars come into view as neatly organized geometric arrangements; long runs of now-mature trees along the park’s southern edge, gridded clusters of newer plantings filling the rough area between the former golf course’s second and third fairways. However, below ground a different, nonlinear narrative is unfolding, entangling tree roots with soil, water, waste and microscopic bacterial life. Poplar trees have fast-growing, wide-spreading, and deep-reaching root structures that are highly effective at drawing up water, stabilizing soil, and absorbing contaminants. It’s what makes them excellent choices for phytoremediation, and this proprietary, genetically engineered variant known as the TN/DN-74 hybrid poplar was developed specifically for even quicker growth and therefore faster intake and processing of toxic impurities.

The subsurface story of the TN/DN—74 exemplifies one of many microhistories of the Park that go unseen. To “see” these, we need different tools and techniques than standard forms of landscape representation can offer. Going underground in this case, to somehow depict the Park’s vertical depths, I have been fortunate to have access to the work of Queen’s geoscientist Dr. Alex Braun and his students, specifically material gathered and created through remote sensing instruments and data visualization strategies. When recontextualized by presentation as hand-sewn marks on geosynthetic textiles atop aluminum poles affixed to sculptural concrete bases, the status of these images as products of culture as much as science and technology is made tangible. The narratives I aim to unearth in LAWNCARE — of wasting, of leisure, of neglect, of various forms of care — are hyperlocal and specific, yet through them we can read larger social and economic forces at work. From synthetic trees to off-gassing metals, the dynamic interplay of biological and cultural life at Belle Park haunts the space with ever-changing spectres that can only be gestured at and provisionally summoned, perhaps by the placement of these somewhat inscrutable flags.

Afterlives

Looking back at this project, I more fully understand how the attempt to enact my own kind of care through an artistic intervention that surfaced important unseen histories also represented its own kind of violence. Although social in conception, and ecological in outlook, an artwork — however public — is also about getting your way. Holding a position, however lightly, within the dynamic flux of all of life’s windblown and rainswept systems. To realize LAWNCARE we cut and hacked, carried and stacked, cajoled and begged, imposed ourselves and our vision on a space where people lived, negotiated the fields where birds and insects produce and reproduce the relations that make up their intersecting lifeworlds. The work, now de-installed, was not maintained, but did leave its trace, a residue of a moment, an ephemeral articulation of care and violence all at once, another microhistorical layer.

Belle Park is a flashpoint for some of Kingston’s toughest, most enduring issues—housing, environment, land use, Indigenous erasure — and LAWNCARE couldn’t, or perhaps even refused, to directly address any of them. It did however deepen my engagement with the space and its human and nonhuman inhabitants, as well as with the broader infrastructures — from its remediation pipes to its informal social networks and the various siloed municipal departments who absolutely did not communicate with each other as we sought approvals for the project. Unearthed – the name of the overall exhibition — certainly did reveal, but as so often with art, it generated more questions than answers.

In golf, a “hazard” such as a sand trap or pond is also considered a feature. This duality speaks to broader ambiguities surrounding how land is cared for (or not), what that care means, and how it is always subject to multiple interpretations and contrasting values. At one point during installation we realized that one of the flag locations was directly adjacent to a small protected area of forest that someone had converted into their home. This moment revealed the true stakes of the project: the significance of the artwork paled in comparison to the daily rigor of survivial experienced by many. More than I could have anticipated, this work made visible to me the real tensions and paradoxes that a public space like Belle Park contains. But we put the flag there anyway. And while I acknowledge that the act (while temporary) might be seen as a marker of conquest or claiming as much as a practice of care, when I returned for de-installation it had not been vandalized or removed. For the weeklong duration of the exhibition, art and home coexisted, perhaps in tension, perhaps oscillating between hazard and feature.

References

Edgeworth, Matt. “The relationship between archaeological stratigraphy and artificial ground and its significance in the Anthropocene.” In Waters, C. N., Zalasiewicz, J. A., Williams, M., Ellis, M. A. & Snelling, A. M. (eds.), A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2014: 395, 91–108.