Lessons from the Water’s Edge

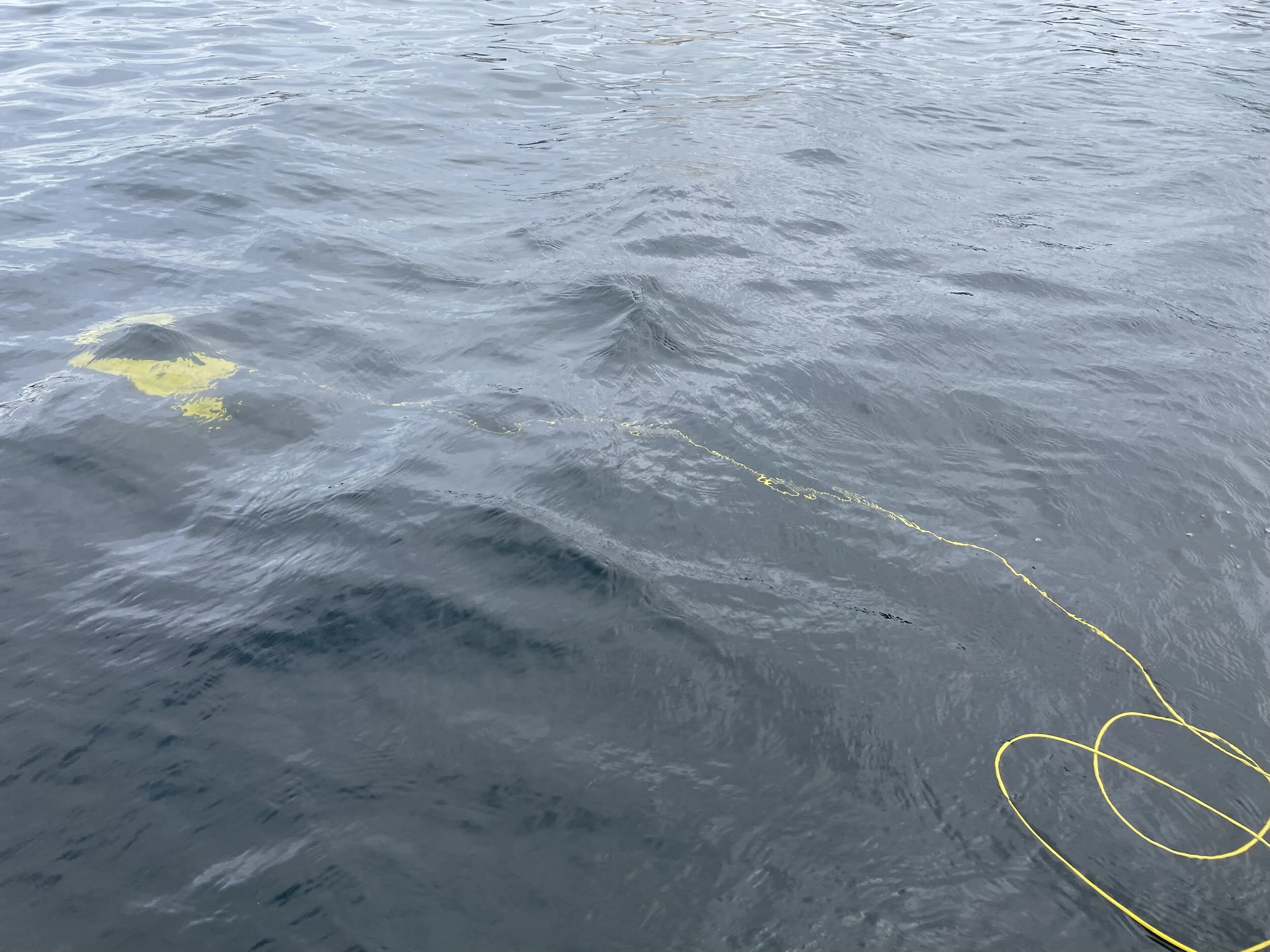

It took six or seven minutes before the camera of the underwater drone found a small school of pumpkinseed sunfish. Despite the exquisite 4K resolution, the image was fairly murky, and if it weren’t for Wenxi — the Biology PhD student who brought and operated the drone — I wouldn’t have been able to identify the fish. This surprised me, not because I am a big expert on fish, but because over the past month I have stared at crisp 3D models of pumpkinseed sunfish for a few hours each week. I should have recognized them.

At the southern edge of Doug Fluhrer Park, where the shore curves out into the Cataraqui River, stands a wooden sign with a fish image stencilled on it. The sign activates our Swimming Upstream AR app, an augmented reality artwork that animates hyper-real images of fish that used to be plentiful in the river. When you aim a phone or a tablet at the sign, you can see the fish swimming happily over the water and around the sign — magic created by digital artist Jenn Norton with 3D fish models available online, some of them generated by the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard.

A couple of times a week I sit on a bench by the sign — behind me the droning sound of cars on the metal grid of the La Salle causeway, in front of me the geese cawing and yacking. I survey the lily pads, the water weeds, and the green-grey water. I see ducks, cormorants, and many geese, but from the bench, I can’t see any fish: even on a cloudy day, the water is really murky. Wenxi explained that murky water often signifies ample organic material, which would suggest we would find more species and more life. But this water is polluted, and in some places toxic, and the fish population thus greatly reduced. Eventually the underwater drone camera also found a young largemouth bass, and a bluegill, but it was striking how few fish we saw even with its hi-tech help.

Back by the sign after the drone adventure I invited a father and his young son to experience the AR piece. The two had just finished fishing for fun (tossing the fish back into the river), and they watched the drone and its images with us. The four-year-old put on the headphones, held onto the iPad, and was simply in heaven. “This is the best thing ever!” he proclaimed, lingering to prolong the experience. After they left, I put the headphones on myself and watched the piece again. The mesmerizing binaural soundtrack, recorded under water right at this spot by Matt Rogalsky, together with the hyper-real images of the fish “swimming” in the water (and in the air, and over the grass), creates a fantastic and slightly out-of-this-world experience. While highly aestheticized, the app is not separate from the environment, but is activated by it, layering the environment with new meanings. This is the beauty of augmentation, which unlike virtual reality (VR), does not separate the viewer from the world, but rather deepens the experience of the space. At the same time, it creates a clarity, for better or worse, that the world itself does not offer.

Our app does not include contextual information. It neither names the fish, nor provides information — such as the fact that the American eel population in the river and in Lake Ontario is at 1% of what it used to be. The documentary filmmaker that I am worried a bit before we launched it, as to whether people would wonder why it is even there. But I am endlessly surprised by a consistent pattern of conversation that emerges as I sit on my bench. People usually ask whether the reason for the decline in fish population is pollution. I answer that as far as I know it is one factor, but overfishing, and the locks system on the St. Lawrence Seaway (which blocks eel migration) are factors as well. Then people ask me what I think about the idea of dredging the river. Kingston residents and its City Council only found out about the Transport Canada plan to dredge highly toxic deposits from the riverbed a couple of months ago. Scientists seem to be divided as to whether it is feasible to remove the toxins without spreading them further down river and into Lake Ontario, and whether the price of disrupting the existing ecosystem is justified. It is a thorny issue, and public discussion will no doubt be ongoing for some time (see River First YGK on facebook).

The dredging plan became public after we started working on the Swimming Upstream AR app, as part of the Skeleton Park Arts Festival, but our audience is making the connection. It is a beautiful reminder to me: when you are in the right place at the right time, let the art be evocative and not didactic. Then the conversation will emerge, not forced, but organic, resonant, and relevant.

— with thanks to Wenxi Feng and Stephen Lougheed, Biology, Queen’s University.